Bank of Slovenia: The measures taken were vital to maintaining financial stability in Slovenia

At a hearing before the Court of Justice of the European Union in connection with the question of the Constitutional Court of the Republic of Slovenia with regard to the validity of the Banking Communication, the Bank of Slovenia gave a detailed presentation of the circumstances in connection with the necessity of taking extraordinary measures with regard to the financial position of five banks that were subject to such measures in 2013, and with regard to one bank in 2014. The Bank of Slovenia explained to the court that the measures taken were vital to maintaining financial stability in Slovenia. The Bank of Slovenia was committed to applying such measures pursuant to the Banking Act (ZBan-1) for the purpose of maintaining financial stability in the country.

The legal basis for the imposition of measures was therefore in place, and Slovenia provided state aid to banks to maintain financial stability in the country and to meet its obligations as a member-state of the EU.

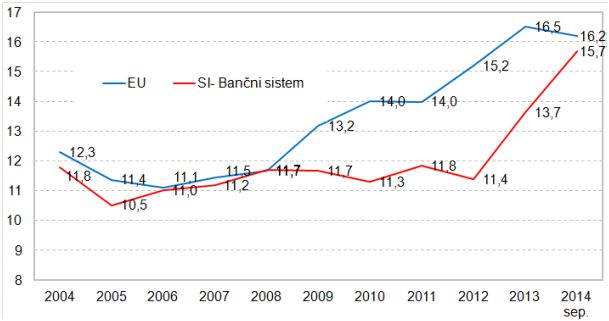

The Slovenian banking sector has faced a capital shortfall since 2008, when the gap between the overall capital adequacy of banks in Slovenia and across the EU began to diverge sharply.

Chart: Gap between capital adequacy of banks in Slovenia and across the EU (average, in percentages)

The overall capital adequacy of Slovenia banks at the end of 2012 was 30% less than the average across the EU, owing to the lack of timely response to the Bank of Slovenia’s calls for recapitalisation. External calls for urgent and immediate measures also became louder in 2012. The increased risk assessment increased the loss of confidence at home and abroad. The European Commission’s warnings went unheeded, but the stress tests in May 2013 revealed a major capital shortfall in the Slovenian banking system.

On several occasions since 2008 the Bank of Slovenia had required the recapitalisation of the banks that in 2013 and 2014 underwent the recovery and resolution procedure, namely NLB, NKBM, Abanka, Banka Celje, Probanka and Factor banka. The shareholders of all the banks had the option of addressing the problem of the capital shortfall themselves, but none of the banks succeeded in increasing its share capital, since the shareholders were unwilling or unable to provide fresh capital, and the banks failed to attract new investors. All the banks requested state aid on a voluntary basis.

To avoid any doubts as to the credibility of its information on the capital needs of the banks that requested state aid, the Bank of Slovenia engaged independent experts to conduct a comprehensive asset quality review at the banks and to make a forward-looking capital adequacy assessment. The conditions of the comprehensive assessment were set out in accordance with the requirements of the European Commission and the ECB. The comprehensive assessment revealed a significantly larger loss at the banks, most notably as a result of a severe increase in the banks’ non-performing claims. This loss meant that the banks were disclosing negative equity.

The aforementioned banks accounted for half of the entire domestic banking sector in terms of total assets, and their simultaneous bankruptcy as a result of insolvency would have led to the collapse of certain other banks, which would have resulted in unmanageable consequences for the economy, political stability and, not least, social rights. The government and the Bank of Slovenia had to take recovery measures to address the insolvency of these banks and to prevent their bankruptcies.

Given the negative equity and the previous failed attempts at private recapitalisation, the last resort for addressing the insolvency of these banks was recapitalisation by the government. The state aid was subject to European Commission approval. Had the requirements with regard to state aid not been met, and had the European Commission not allowed the implementation of these measures, the economy and the stability of the entire country would have been threatened. Without the swift approval of state aid, the stabilisation of the Slovenian banking system would have been rendered impossible, thereby seriously threatening the real economy. Had the European Commission not allowed the state aid requested by the banks, bankruptcy proceedings would have been initiated against the banks. The independent experts had determined that in light of the banks’ financial position, their shares and other instruments were entirely worthless, since in bankruptcy proceedings all the banks’ residual assets would have to have been used to repay their depositors and senior creditors, leaving nothing for the shareholders and holders of subordinated instruments. (For more on this, see the report submitted by the Bank of Slovenia to the National Assembly in March of this year.)

For the banks to be able to receive the state aid that was vital to the stabilisation of their operations, and to satisfy the requirements of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union and the European Commission’s Banking Communication that the aid be kept to a minimum, the measure of covering the capital shortfall first via share capital and subordinated instruments had to be carried out before funds from the government could be contributed to recapitalisation. Only in this manner could a contribution to the coverage of losses be provided by holders of equity and subordinated capital outside of bankruptcy. Total cancellation was necessary, as the shareholders and holders of subordinated instruments would not have even been partially repaid in the event of the bank’s bankruptcy. Had the contribution by shareholders and holders of subordinated instruments not been provided to this extent, the recapitalisation of the banks via state aid would not have been permitted under EU rules on state aid.

The Bank of Slovenia was obliged to uphold the applicable legislation in the bank recovery and resolution procedure, including the new Banking Act, which was adopted by the National Assembly in the second half of 2013 and sets out the measures of cancellation and conversion of eligible liabilities (shares and subordinated debt instruments). Had the Bank of Slovenia not applied the aforementioned measure in connection with the bank recovery and resolution in 2013 and 2014, the recapitalisation of the banks by the government would not have been allowed, which would, as stated, have resulted in the bankruptcy of the aforementioned banks, the adverse consequences of which are described above.